Since 2001 immigration authorities around the world have been using accent and language tests to determine the validity of asylum claims made by thousands of people without identity documents in Australia, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. In most circumstances a private Swedish company is contracted and during a phone interview between this company and the asylum seeker the claimant’s voice is analysed to assess whether the voice and accent correlate with the claim of national origin.

Over 29 and 30 September 2012, a group consisting of linguists, graphic designers, artists, researchers, activists, refugee and art organisations and a core group of Somali asylum seekers, who have all been rejected because of the analysis of their language/ dialect or accent by the Dutch immigration authorities, met to discuss the controversial use of language analysis to determine the origin of asylum seekers.

The meeting was called because we feel that these accent tests are becoming increasingly unjust and prevalent in denying legitimate claims of asylum. The tests are relatively unheard of outside of specialists working in the field and creating these images is a way of disseminating its existence. We hope that when we know of such a policy, we might reflect on what our own hybrid accents say about our place of birth, how we change and adapt our voices in different social situations and how complex our accents would be after a lifetime of migration.

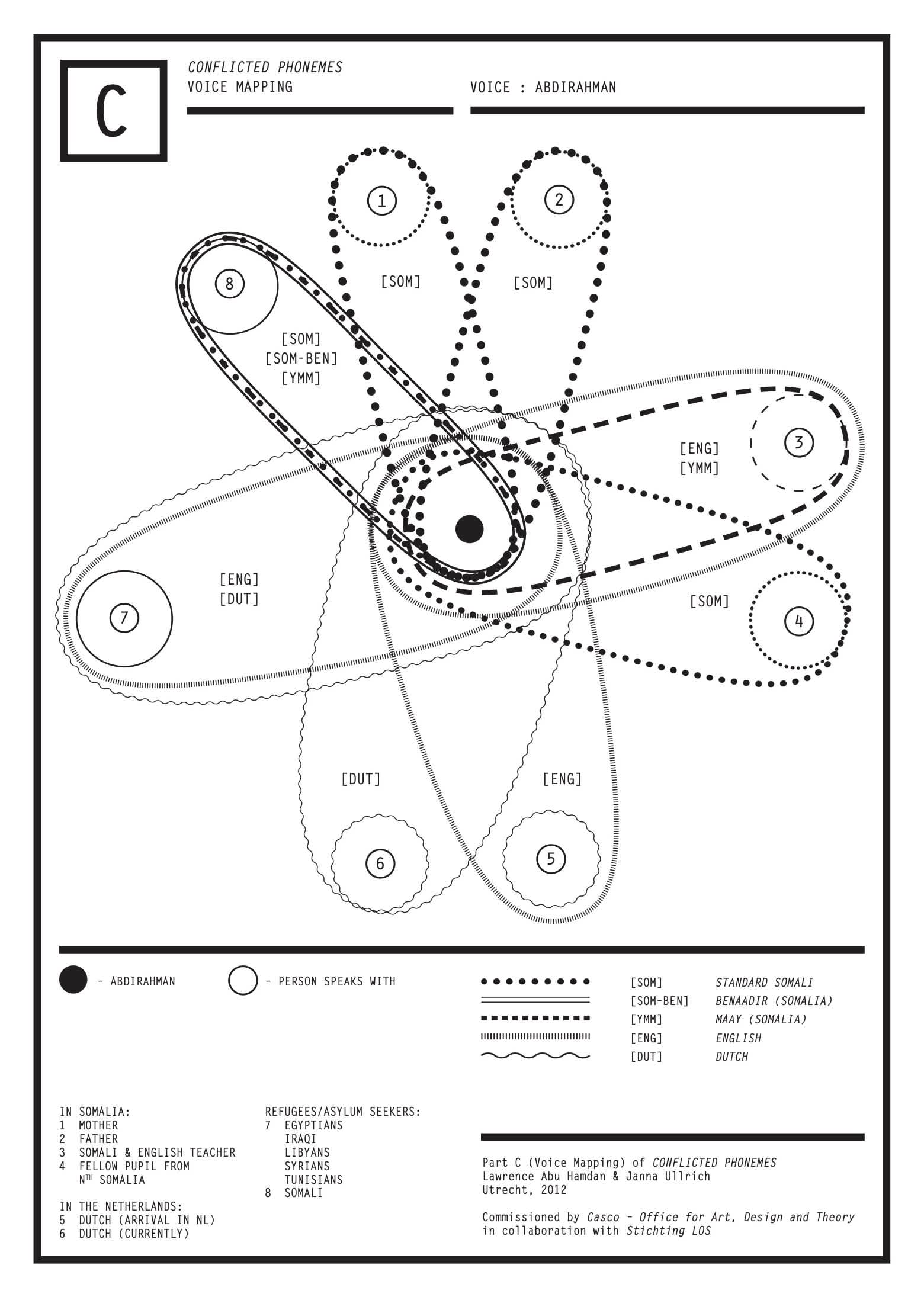

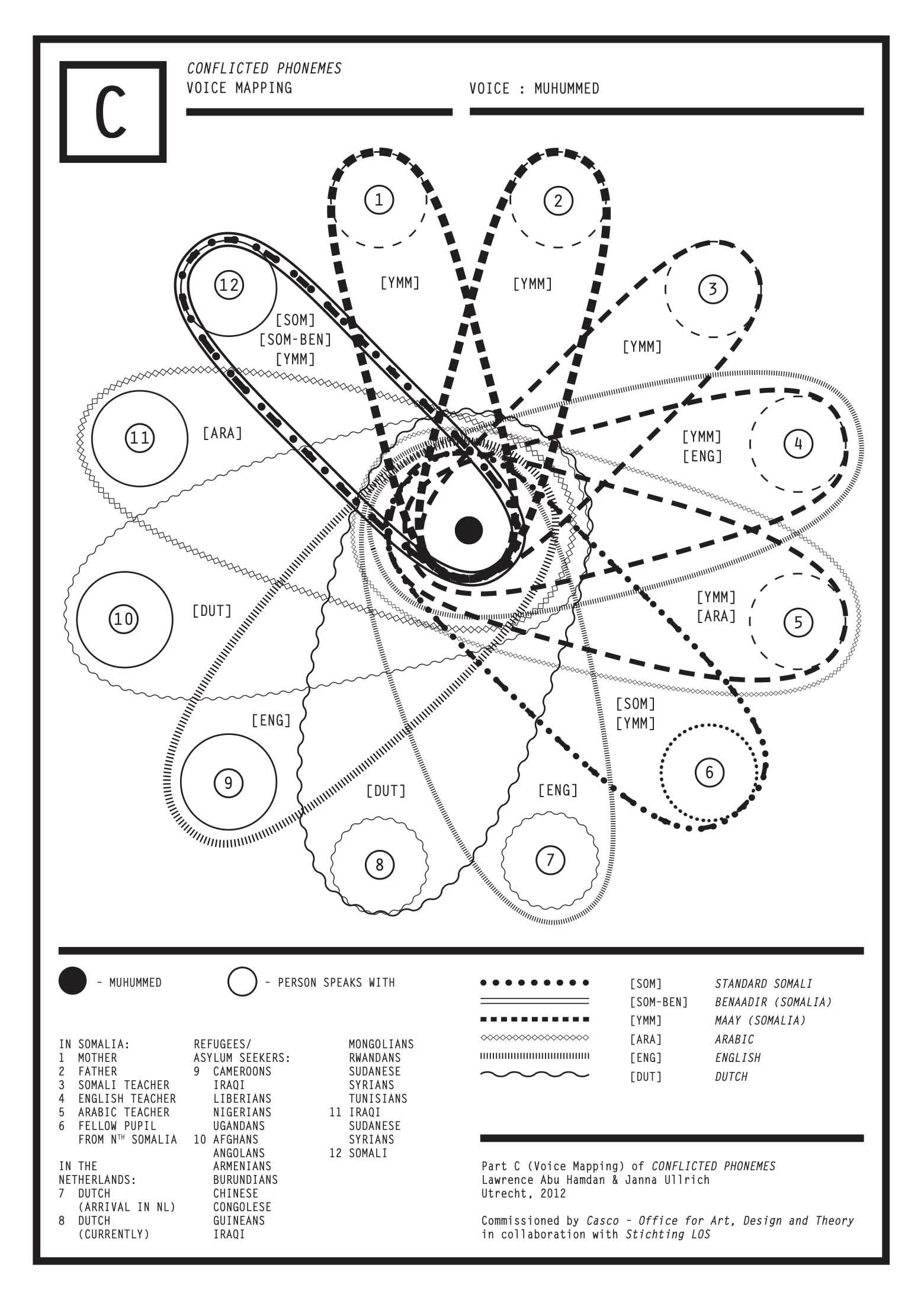

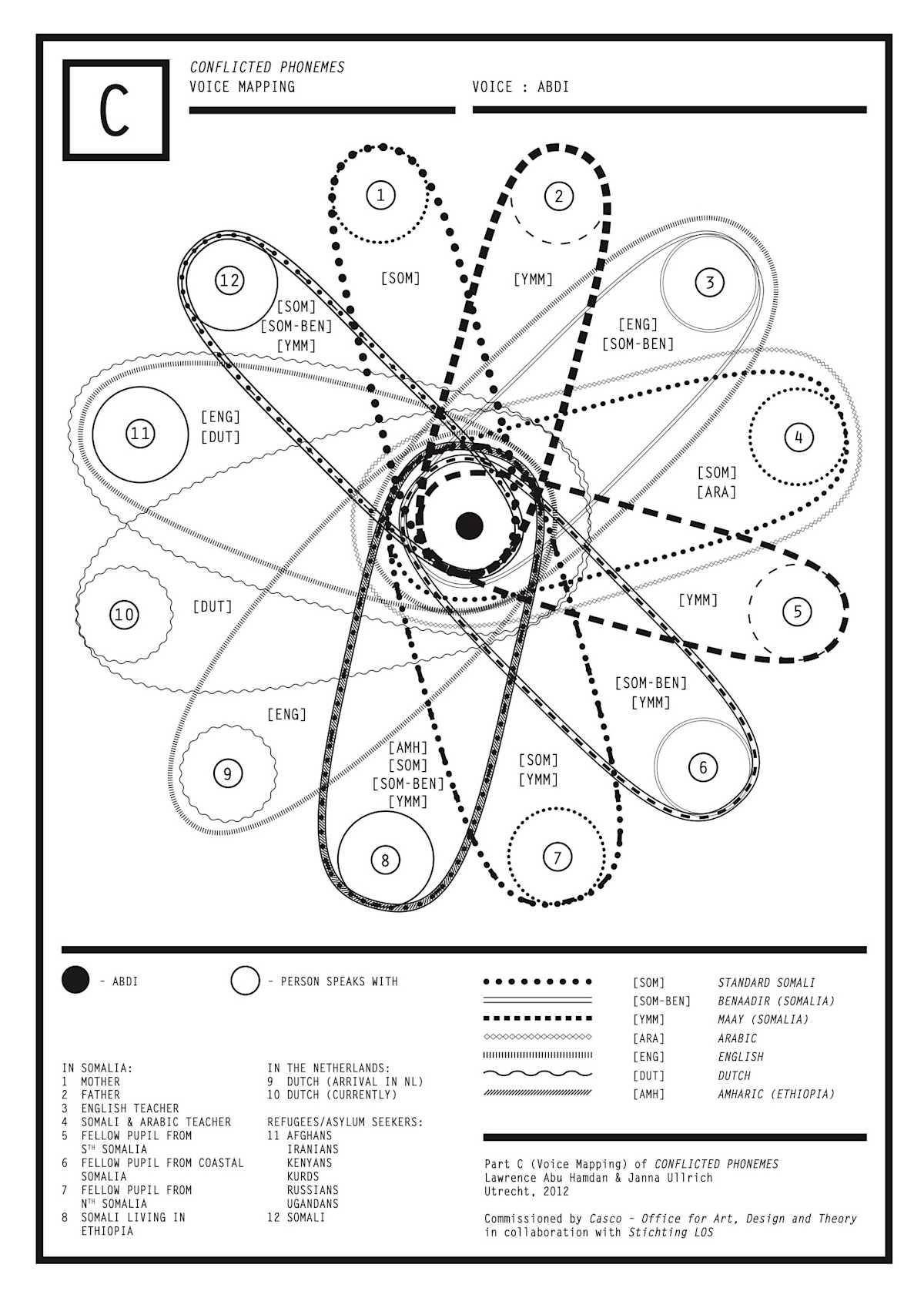

Often the result of these tests hinge on a couple of words and unable to contest the results of their language analysis, the collection of maps exhibited here intend to offer the rejected/silenced asylum seeker an alternative and non-vocal mode of contestation.

In particular such accent tests wrongfully target the Somali community; common results of the tests find that the Somali applicants are from the north rather than the south of the country, pinpointing them conveniently to the small pockets of safe and habitable regions. These maps intend to demonstrate how the history of Somalia, its ungovernability and its 40 years of continual migration and crisis, have made an impact on people’s way of life as well as their way of speaking. Usually maps are abstracts, they reduce the complexity of the issue to a digestible form, yet here we felt it was important to rather show how complex the situation in Somalia is and how consequently irreducible the voices and biographies of those who are fleeing from conflict and famine.