It is obvious from the map, after Kanjiza, there is still another Serbian town called Martonos. It is coloured with a yellow rectangle, after we pass this one you will be going toward the border.

Once you exit the second town, the forest will be on your right, on your left you will see a hill, as you are in a valley. The hill continues to the next town which is Szeged. It won’t be obvious that you got into Hungary, you will know that you are in the Hungarian territories, and you cross the border, once you get to the white and red checkpoint. On the left of the checkpoint there is a small stream of water (small waterfall), marked in yellow.

If the police come, you escape from the entrance where you came.

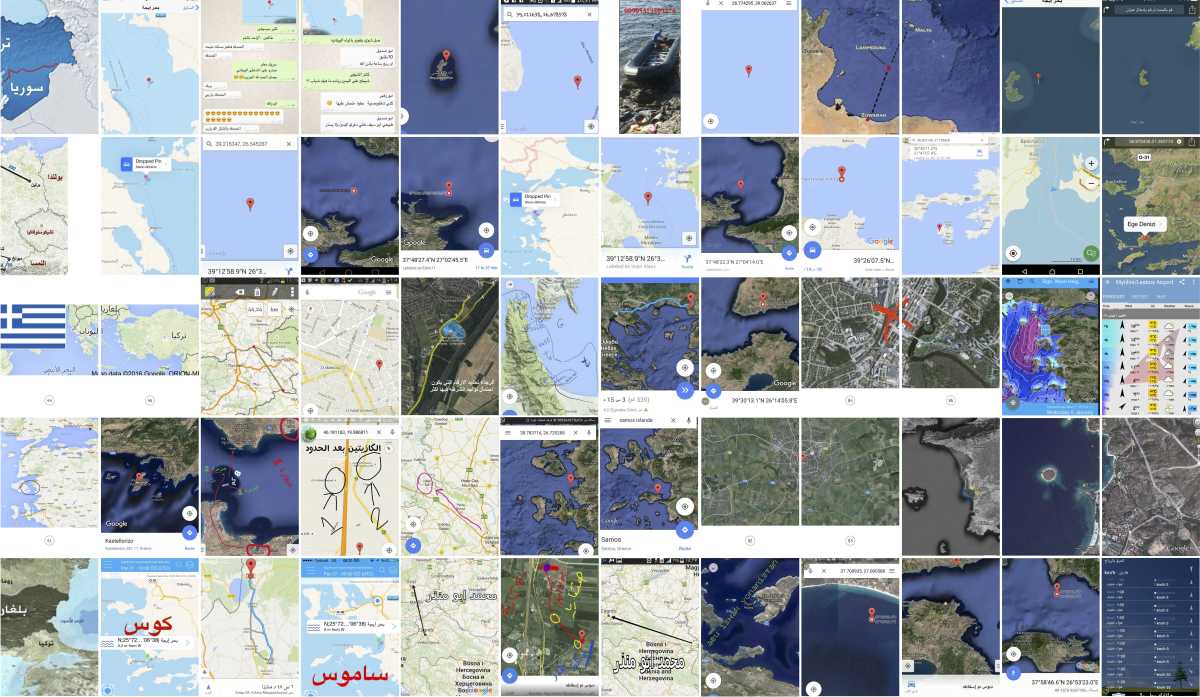

Follow the directions above to travel from Serbia to Hungary. They appear on social media platforms with many other digitally native and often manually annotated maps, circulated among the people who seized the global imagination in the summer of 2016: the primary protagonists of the ‘refugee crisis’. These maps took their travellers across the Aegean Sea, guided them around the Idomeni border from Greece to Macedonia, and directed them through the woods from Skopje to Serbia. They told how much the bus ticket cost, or the train fare; where the police and the border patrols were more – or less – friendly; which camps to avoid. Which hill to climb, which river to cross, which town to go around, where to sleep, when to start walking, when do you know you’ve arrived?

How much longer do you need to keep going? What are the rights that you do, or do not, have? What is shown by these maps and the media through which they circulate is not only the scope and length of the journey, its risks and dangers, but also that there is a migrant support network that shares information and knowledge with those making the journey, operating in parallel to states, NGOs, volunteers and human rights activists.

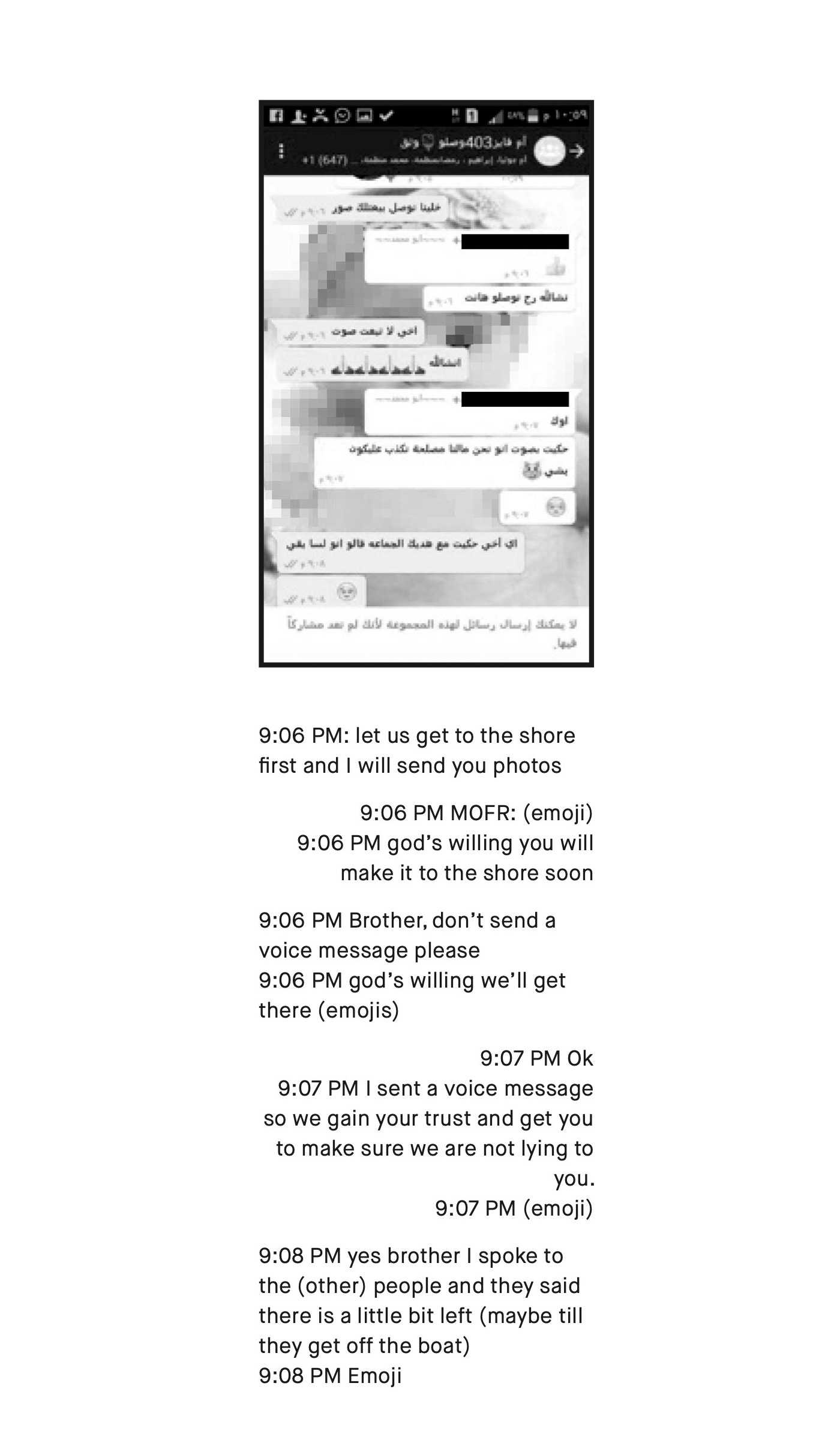

9:58pm steer to the right very quickly

9:58pm to the right god have mercy on your grandparent who told you to go left

9:58pm (angry emoji) or would you like to sail few more kilometers in the water

9:58pm steer to the right quicky

9:59pm after two minutes give me a location

9:59pm (photo) Okay, that’s cool

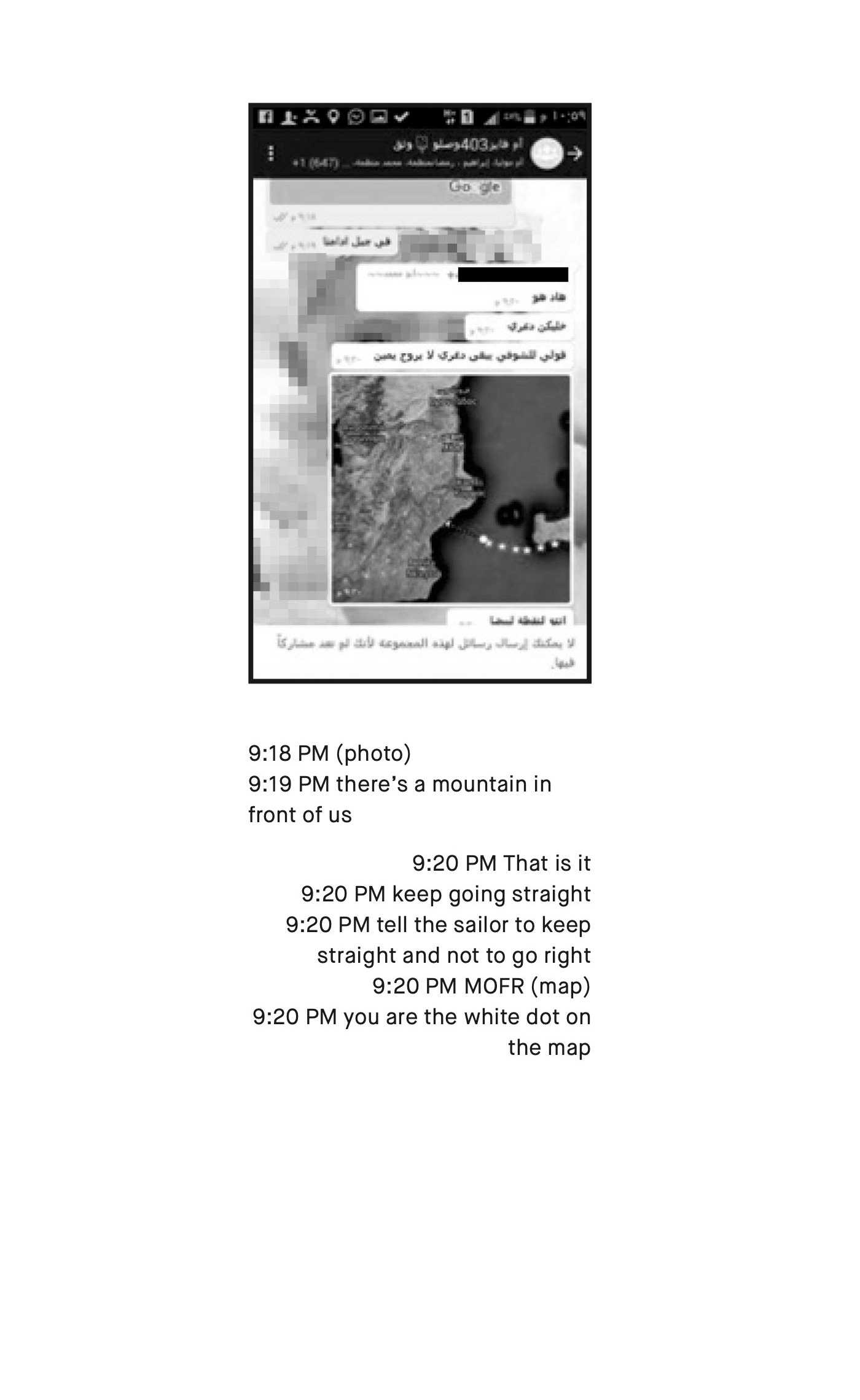

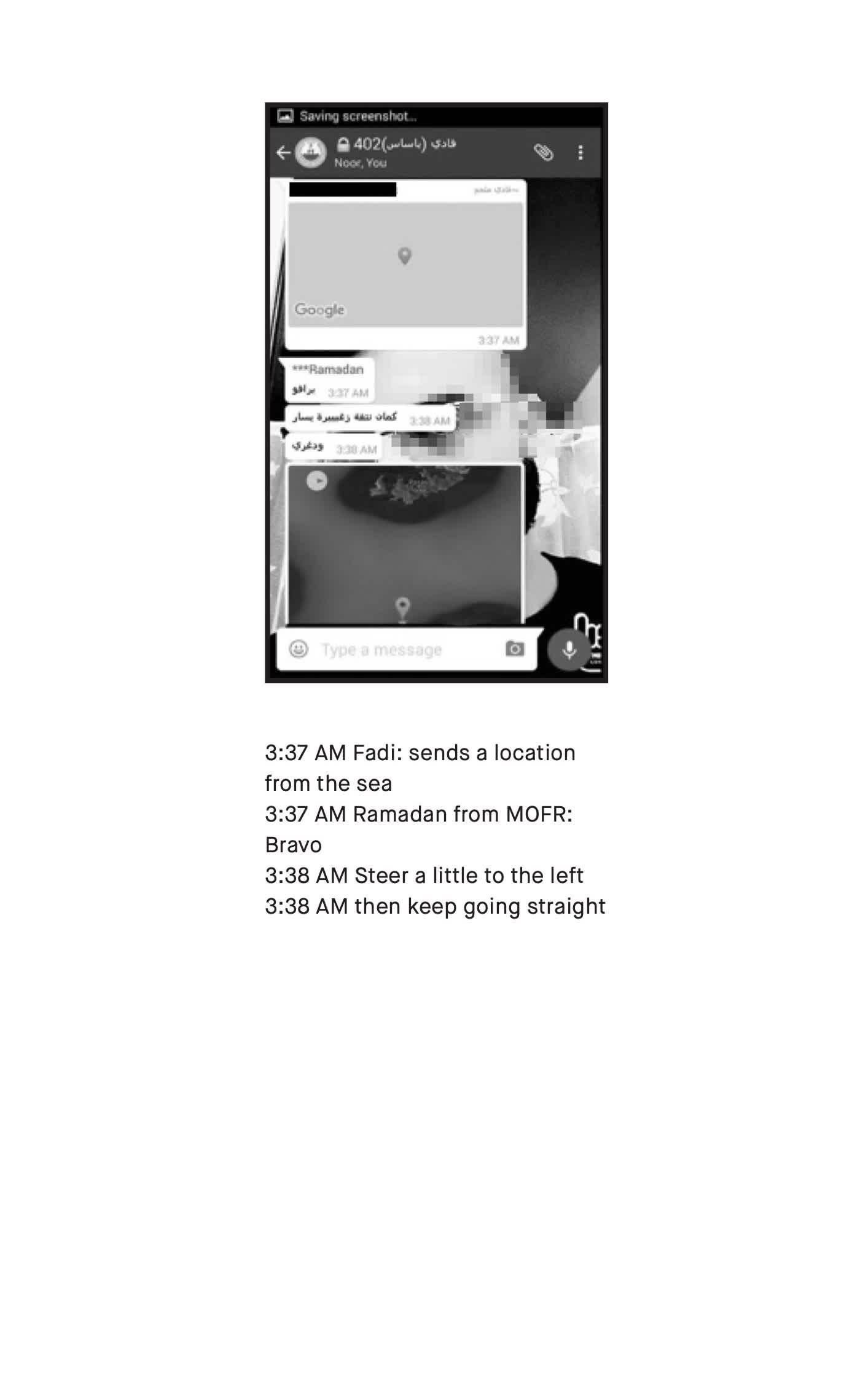

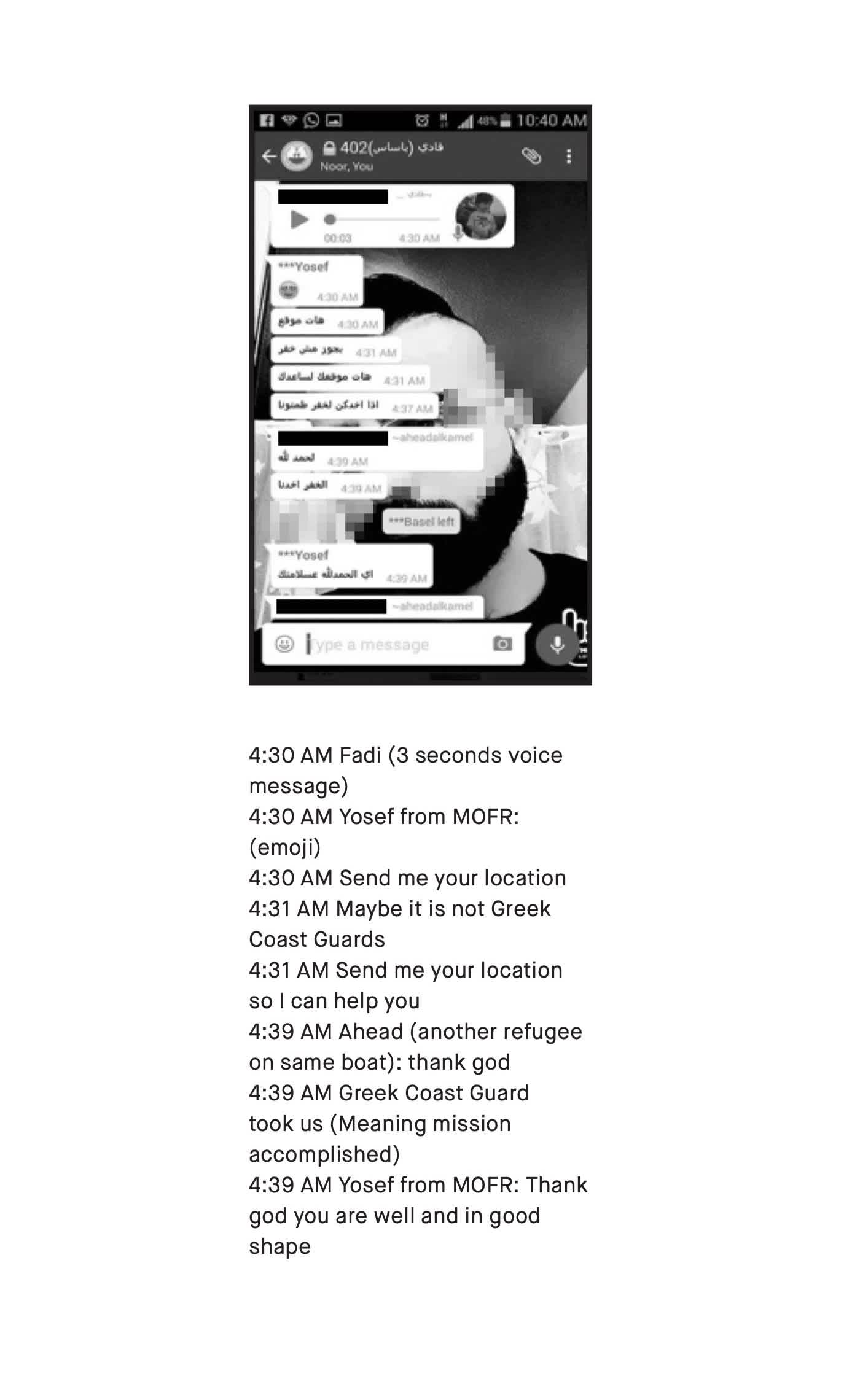

This conversation is extracted from an online archive of the communications between migrants sailing across the Aegean Sea and the volunteer refugee organisation Maritime Organisation for Following up and Rescue (MOFR). From 2014 to 2016, this group of 15 volunteers – mostly Syrian refugees spread out over Turkey, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and Europe – assisted and directed fellow Syrian asylum seekers travelling by sea from Turkey to Greece through WhatsApp messages. MOFR’s remote guides would receive messages from groups leaving the Greek coast, ask the migrants for their position, and then – using maps and location sharing – attempt to direct them safely to their destination.

These maps attempt to realise and instantiate a basic right to migration. They are testaments to claiming the right to move. They are both an itinerary to be accomplished and a document of a completed journey; they bear witness and respond to the shifting regimes and technologies of fortification, to the intimidation, weather, hospitality, law and violence that structure and govern possible journeys. These maps are created one by one and piece by piece by the crowd following their routes – many bear very precise indexical traces (whether dropped pins or geotagged metadata) of where and when they came into being. They are digital traces of complete journeys, but they are also traces that are missing from various cartographic systems designed and commissioned to monitor – and eventually control and prevent – migrants’ movements. Live updates of the flow of migrants (accessible through platforms such as I-MAP) only show the interrupted movements of the apprehended travellers.

The maps also are indications of a parallel system of movement that does not – at least not simply – abide by the international regimes of documents, visas, passports or identification papers. They are documents of the undocumented, of unregulated sans papiers travel that does not follow the conventions and protocols put in place to control the movement of people across international borders. Missing from both migrant maps and official maps are the locations of the unregulated detention houses where smugglers keep travellers before and after every crossing, until the funds for the next stage of the journey are transferred. Much like how police and border control often confiscate migrants’ phones before detention, there is similarly little possibility of documentation from the black houses. While the former is stationary, the latter is itinerant.

Djordje Balmazovic from Škart collective has been making maps in collaboration with migrants in refugee camps across Serbia. When the artist asked a refugee what papers he presented at the border from Afghanistan to Pakistan, or from Pakistan to Iran, or from Iran to Turkey, he responded: ‘you don’t need papers when you are travelling illegally’. It’s a truism that documents lose their pertinence when you’re operating outside the international legal systems of travel, migration and control. Yet this confronts us with the reality that if these ‘illegal’ journeys take place, if the right to movement is nonetheless practised, then such journeys also bring into question the territorial, linguistic and ethnic foundations of citizenship and modern nation states. As Arjun Appadurai has discussed, these types of migratory movements are not accounted for in conventional narratives, since they are based not in inherited rights from the past, nor in the achievements of the present (such as work, marriage, student status), but rather in the future: in ‘the aspiration for a better home, a safer life, a more secure horizon’.1

The maps show that today, claiming to be human and to have rights is powerfully linked to migration. Movement, therefore, is essential to asserting your humanity. These claims are not only made at the border, or in the camp, or at the train station, or at the asylum hearing: the journey itself is a way of exercising and realising the right and the claim to recognition. In the Bogovda camp in Serbia, in response to Balmazovic’s question ‘why did you make the journey?’, a 16 year old Afghan refugee said: ‘in search of equality and rights’. Call it ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’, or ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ – two other foundations of modern nation states in which people seek refuge. Such foundations are, at the moment, all too often ignored. It is here that the birth, blood, and kinship grounds of citizenship confront what gave birth to the state to begin with – freedom from despotism, tyranny, colonialism, or authoritarianism.

In a workshop in Zaragoza, Spain, organised by anthropologist and geographer duo Maribel Casas- Cortes and Sebastian Cobarrubias, refugees who had successfully sailed across the Mediterranean noticed discrepancies between the official maps and their own paths, and decided to draft ‘our own map of migration routes’. The migrants’ maps were spread, shared, and constantly updated across various communication platforms; they are instances of ‘mapping on our own terms’. On these terms, however much in flux, migrants are transforming the vocabulary and cartography of states, territory and citizenship.